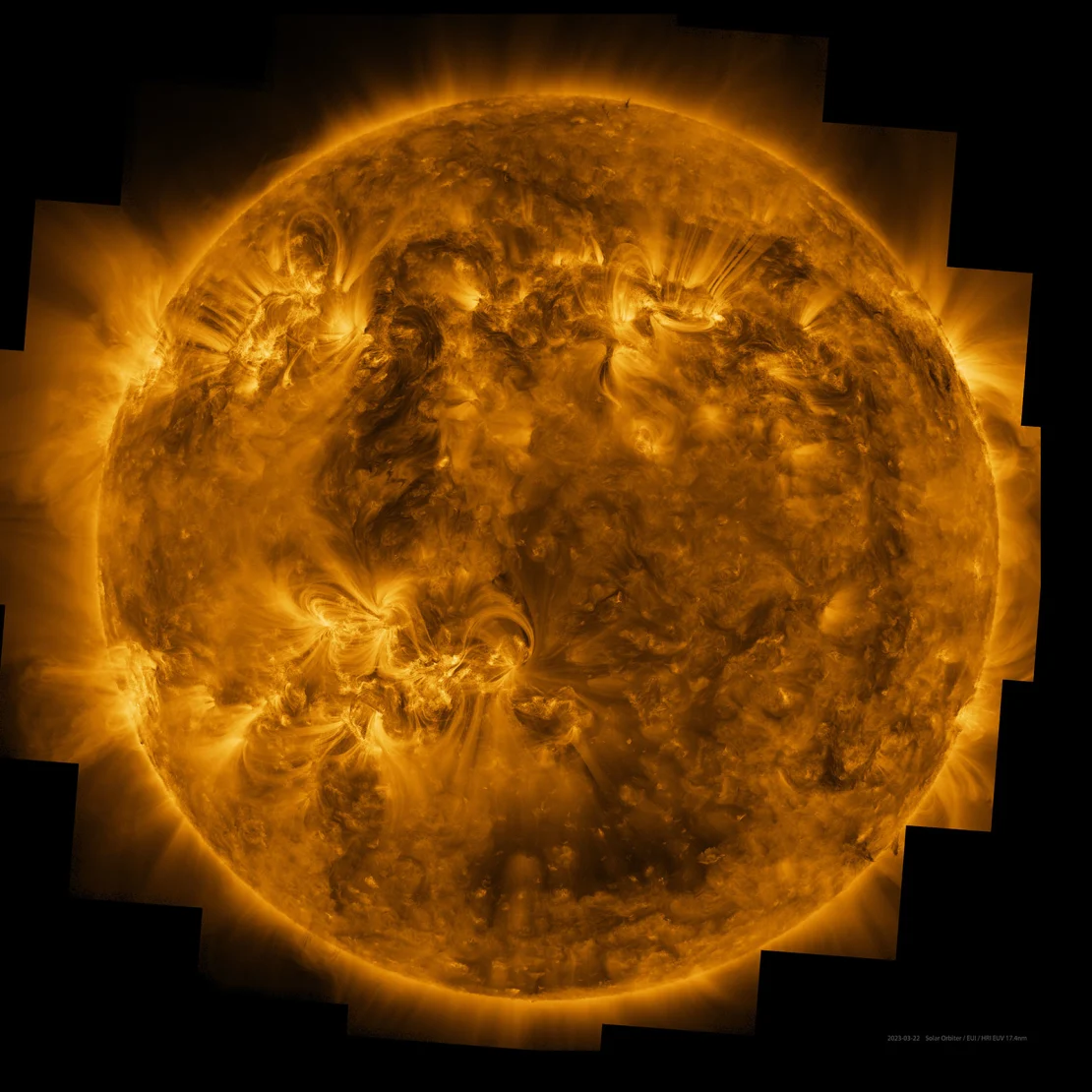

The Solar Orbiter mission, a joint venture between NASA and the European Space Agency, has recently provided the highest-resolution images of the sun’s visible surface ever captured. These images, taken on March 22, 2023, reveal detailed features of the sun, including sunspots and the movement of charged gas, or plasma, that constantly shifts in its atmosphere.

The new images offer heliophysicists an unprecedented opportunity to study the sun’s dynamic processes, potentially unlocking new insights into its behavior and structure.

To capture these stunning images, the Solar Orbiter used two of its six specialized instruments: the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) and the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI). The spacecraft was positioned 46 million miles (74 million kilometers) from the sun, allowing it to observe various phenomena in great detail. These instruments provided views of the sun’s magnetic field dynamics and the outer solar atmosphere, known as the corona, which is much hotter than the sun’s surface.

The Solar Orbiter, launched in February 2020, orbits the sun at an average distance of 26 million miles (42 million kilometers).

In conjunction with NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, it is part of a new wave of missions designed to answer fundamental questions about the sun, such as the sources of solar wind and the mystery behind the extremely high temperatures of the sun’s corona. While the Parker Solar Probe will get much closer to the sun, the Solar Orbiter is specifically tasked with taking the closest-ever images of the sun’s surface.

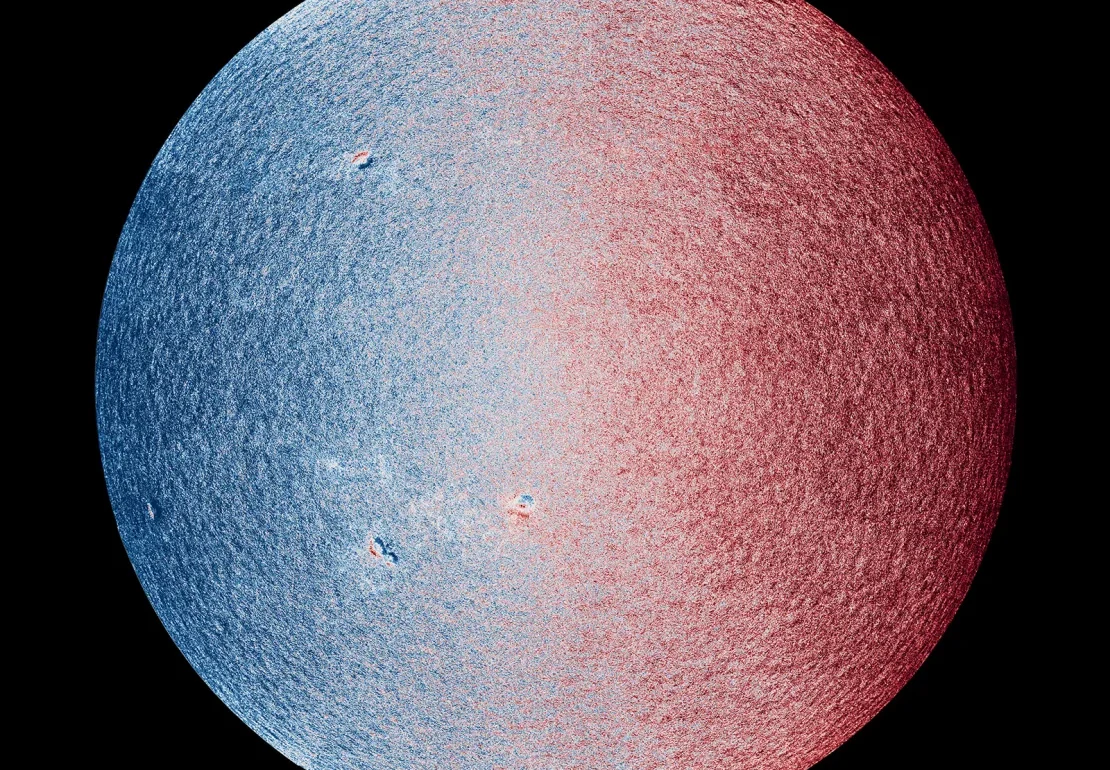

The images captured by the Solar Orbiter reveal intricate details of the sun’s structure. The PHI instrument provided the highest-resolution images of the sun’s photosphere, the visible surface where most of the sun’s radiation is emitted.

The images show sunspots—cooler, darker regions on the surface caused by intense magnetic fields—and magnetic field concentrations in these sunspots. Additionally, scientists used velocity maps to study how material moves on the sun’s surface, highlighting the effects of solar rotation and magnetic disturbances.

Meanwhile, the EUI instrument captured images of the sun’s corona, a hot, glowing plasma that extends far beyond the surface. The corona’s temperature, which reaches over 1 million degrees Celsius, remains a mystery to scientists, as it is much hotter than the sun’s surface. These images of the corona provide valuable insights into the behavior of the sun’s outer atmosphere, especially the connection between the corona and sunspots.

The images come at a pivotal time, as the sun has reached the solar maximum, the peak of its 11-year solar cycle. During this period, the sun’s magnetic activity intensifies, and sunspots become more numerous. These heightened solar activities, such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs), can disrupt space weather and impact Earth’s technology.

The Solar Orbiter’s observations during this active period will help scientists understand space weather and its effects on Earth, including its potential impact on power grids, GPS, and satellite communications. The images also offer a unique opportunity to study auroras, which are caused by energetic particles from solar storms interacting with Earth’s atmosphere.