For nearly four centuries, the story of the Batavia shipwreck has been told as a tale of calculated evil—a heretical merchant named Jeronimus Cornelisz orchestrating a brutal massacre that claimed over 100 lives on remote Australian islands in 1629. This narrative, preserved in the journals of Commander Francisco Pelsaert, has inspired historians and modern media, from reality TV shows to psychological thrillers.

However, a groundbreaking new theory challenges this long-accepted account, suggesting that what unfolded on those desolate coral islands wasn’t premeditated mutiny but rather a catastrophic breakdown of civilization driven by starvation and desperation. Dutch cultural psychologist Jaco Koehler’s research, published in the International Journal of Maritime History, proposes that confirmation bias and torture-extracted confessions may have distorted our understanding of one of Australia’s most horrific maritime disasters.

A Voyage Doomed from the Start

The Dutch East India Company’s flagship Batavia departed Holland in October 1628 on its maiden voyage to the East Indies, carrying over 300 souls and valuable cargo, including silver coins. From the outset, tensions simmered between Commander Francisco Pelsaert and the ship’s captain Ariaen Jacobsz, whose relationship had soured during previous encounters in India. Adding to the volatile mix was under-merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz, a bankrupt pharmacist fleeing the Netherlands due to his heretical beliefs and connections to alleged Rosicrucian followers.

On June 4, 1629, disaster struck when the Batavia crashed into Morning Reef near the Houtman Abrolhos Islands off Western Australia’s coast. The survivors, numbering around 268, found themselves stranded on small, waterless coral islands approximately 60 kilometers from the mainland. Desperate to find fresh water and organize rescue efforts, Pelsaert departed with Jacobsz and 46 others in the ship’s longboat, promising to return with help.

Three Months of Terror

What transpired during Pelsaert’s three-month absence has traditionally been portrayed as a reign of terror orchestrated by Cornelisz. According to historical accounts, Cornelisz seized control of the survivors, confiscated weapons, and systematically murdered approximately 125 men, women, and children.

The traditional narrative describes calculated cruelty: survivors were tricked into believing they could find water on distant islands, only to be murdered by Cornelisz’s accomplices, while others were simply thrown overboard or bludgeoned to death.

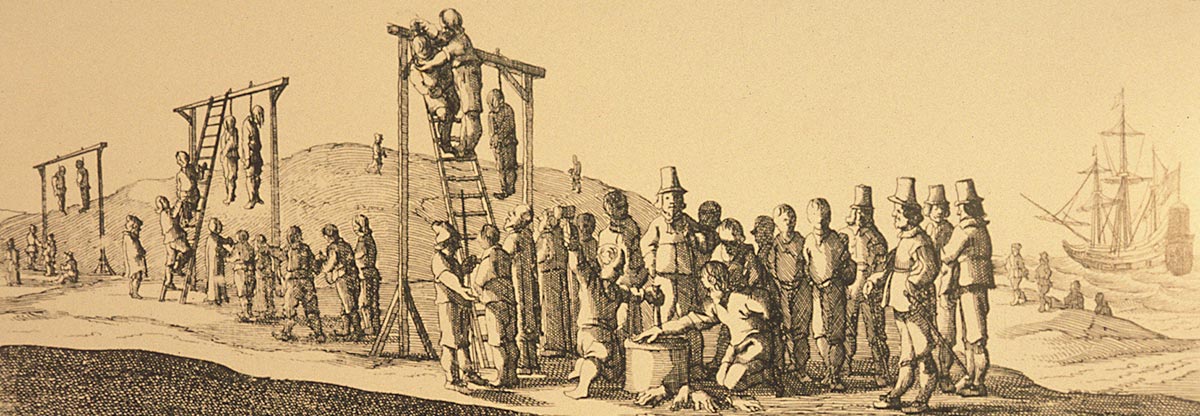

The massacre only ended when a group of soldiers led by Wiebbe Hayes, who had been marooned on West Wallabi Island, discovered fresh water and food sources. When Cornelisz attempted to eliminate this threat to his authority, Hayes captured him, bringing the bloodshed to a halt just as Pelsaert returned with a rescue ship.

A Revolutionary Reinterpretation

Jaco Koehler’s alternative theory fundamentally challenges this accepted narrative. His research suggests that rather than premeditated evil, the massacre resulted from social collapse triggered by extreme survival conditions. Koehler argues that with too many people and insufficient resources, combined with the power vacuum created by Pelsaert’s departure, desperate survivors formed gangs that resorted to theft, intimidation, and ultimately murder to secure food and water.

Crucially, Koehler questions the reliability of the evidence used to construct the traditional narrative. He points out that Pelsaert served as both judge and prosecutor in trials where he had abandoned the survivors—a situation that could have motivated him to deflect blame. Moreover, many confessions were extracted through waterboarding and other torture methods, casting doubt on their accuracy.

Archaeological Evidence and Scholarly Debate

Recent archaeological excavations led by Professor Alistair Paterson from the University of Western Australia have uncovered significant evidence from the islands, including mass graves containing the remains of 12 victims and possible gallows sites. These findings provide valuable insights into the survival and burial practices of the survivors.

However, leading archaeologists remain skeptical of Koehler’s famine-driven theory. Professor Wendy van Duivenvoorde from Flinders University acknowledges the research as “fascinating” but questions why survivors didn’t relocate to resource-rich islands if survival was their primary motivation. The archaeological team notes that some islands had accessible food sources and fresh water, undermining the starvation hypothesis.

Rethinking Historical Narratives

Koehler’s work raises profound questions about how we interpret historical violence and the psychological forces at play during extreme crises. His theory suggests that accepting the narrative of individual evil may be more comfortable than confronting the disturbing possibility that ordinary people can descend into savagery when social structures collapse.

While the debate continues among scholars, this reexamination of the Batavia massacre demonstrates the importance of critically analyzing historical sources and remaining open to alternative interpretations, even of seemingly well-established events.