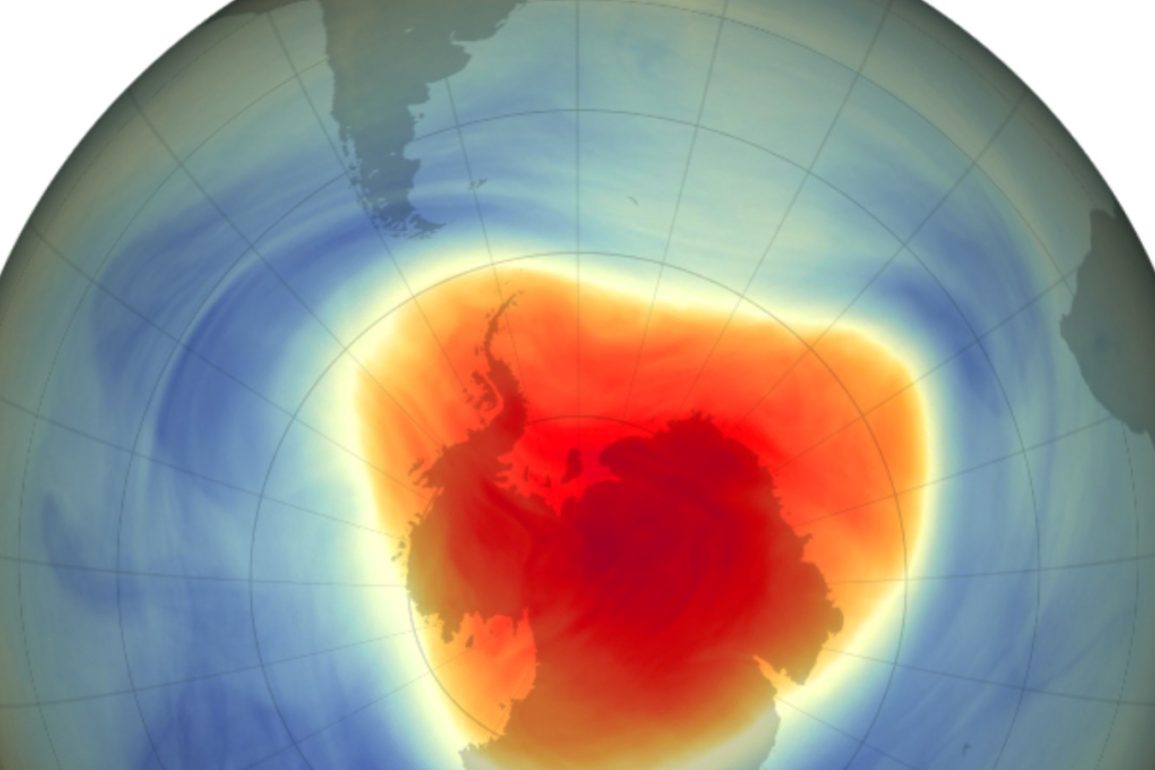

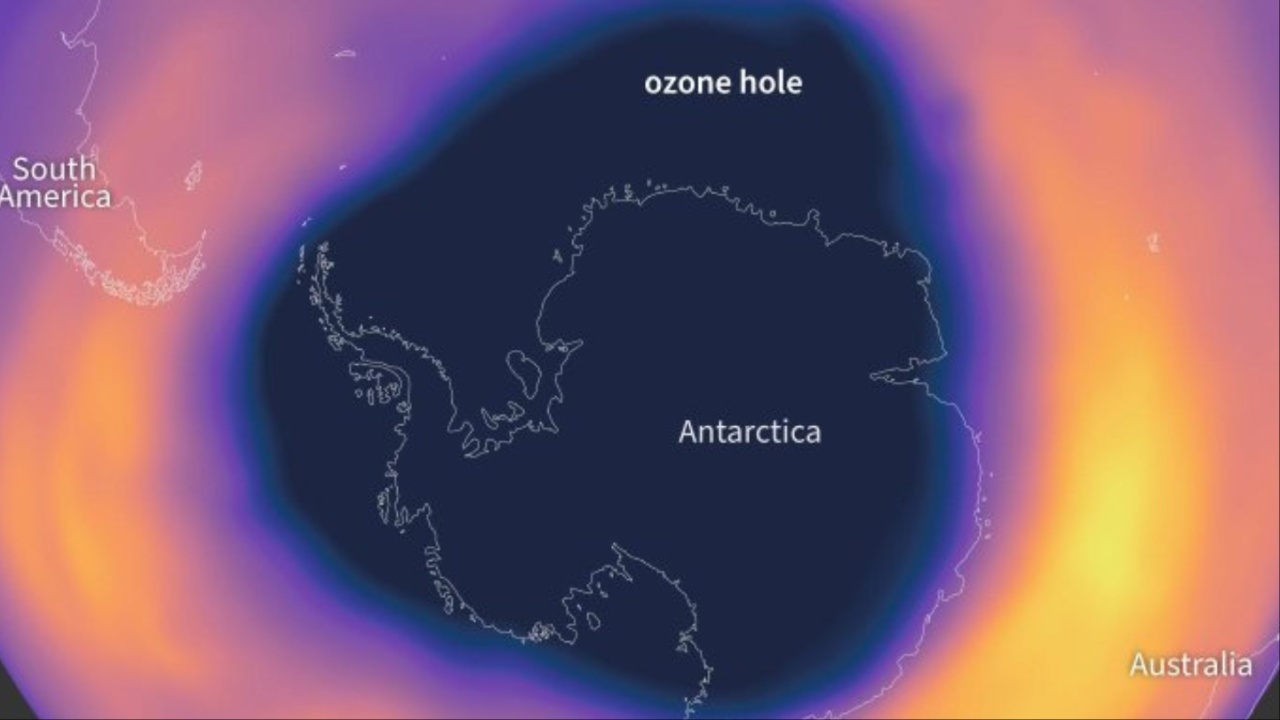

In 2024, scientists observed a significant improvement in the size of the Antarctic ozone hole, which was ranked the seventh smallest since recovery efforts started post-Montreal Protocol. Monitoring data from NASA and NOAA show that the hole, which is seasonally present from September to October, averaged about 20 million square kilometers, with a peak of 22.4 million square kilometers in late September.

This reduction aligns with trends indicating a gradual recovery of the ozone layer, potentially leading to full restoration by 2066 if current efforts to reduce harmful chemicals continue.

The ozone layer depletion has historically been measured using Dobson Units (DU), a metric that represents the concentration of ozone in a column of Earth’s atmosphere. The 2024 maximum ozone hole extent showed areas with concentrations below 220 DU, which qualifies as a “hole.”

In comparison to previous years, the ozone layer’s health has improved due to a reduction in chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) levels. CFCs were once widespread in products like coolants and aerosol sprays, causing significant ozone depletion, but their use has been curtailed under international agreements.

Global efforts to phase out CFCs have played a pivotal role in the ozone layer’s gradual recovery. The Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987, mandated the reduction of CFCs, which has led to a dramatic decrease in the release of ozone-depleting substances.

While the 2024 ozone hole was relatively small, scientists note that CFCs already present in the atmosphere will continue to impact the ozone layer for decades, as they are slow to degrade. This year’s relatively moderate ozone hole demonstrates progress, yet full recovery remains a long-term goal.

The thinning of the ozone layer remains a concern because it protects the Earth from harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. In areas where the ozone layer is depleted, increased UV radiation exposure can lead to higher rates of skin cancer, cataracts, and other health issues.

It also impacts ecosystems, reducing agricultural yields and affecting marine life. In the 1980s, scientists discovered that human-made chemicals, particularly CFCs, were contributing to drastic ozone depletion over Antarctica, which led to international action to curb their use.

Monitoring efforts continue to play a crucial role in tracking the ozone layer’s health. NASA and NOAA use satellites, such as Aura and NOAA-21, as well as weather balloons from the South Pole, to measure ozone levels.

This year, the lowest concentration measured was 109 DU, compared to a record low of 92 DU in 2006. Scientists aim to achieve pre-1979 ozone levels of around 225 DU above the Antarctic, but much work remains. The gradual decline in the ozone hole’s size is encouraging, yet it highlights the ongoing need for global commitment to environmental recovery efforts.