If your phone has been buzzing with unsolicited political messages this election season, you’re experiencing a perfectly legal loophole in Australia’s digital communication laws. The flood of texts from parties like Clive Palmer’s Trumpet of Patriots has sparked widespread outrage, with many Australians questioning how these messages bypass the same spam protections that shield us from commercial marketing.

The reality is both simple and frustrating: political parties operate under completely different rules than businesses when it comes to electronic communication. While you can easily unsubscribe from marketing emails and register for the Do Not Call list to avoid telemarketing, political campaigns face no such restrictions. This exemption, embedded in legislation nearly three decades old, continues to allow parties to bombard voters with messages that would be illegal if sent by any commercial entity.

The Legal Framework Behind Political Messaging

Australia’s approach to regulating electronic communication relies on three key pieces of legislation, but political parties enjoy broad exemptions from all of them. The Spam Act 2003 typically requires organizations to obtain consent before sending marketing messages and mandates easy unsubscribe options. Similarly, the Do Not Call Register Act 2006 allows individuals to opt out of telemarketing calls, while the Privacy Act 1988 governs how personal information is collected and used.

However, political parties and their representatives are largely exempt from these protections when conducting what the law terms “exempt political activities”. This means that even if you’ve registered your number on the Do Not Call list, political parties can still legally send you unsolicited text messages without providing any way to opt out. The exemption extends to political parties, politicians, candidates, and their contractors and volunteers, creating a comprehensive shield from the spam and privacy laws that govern everyone else.

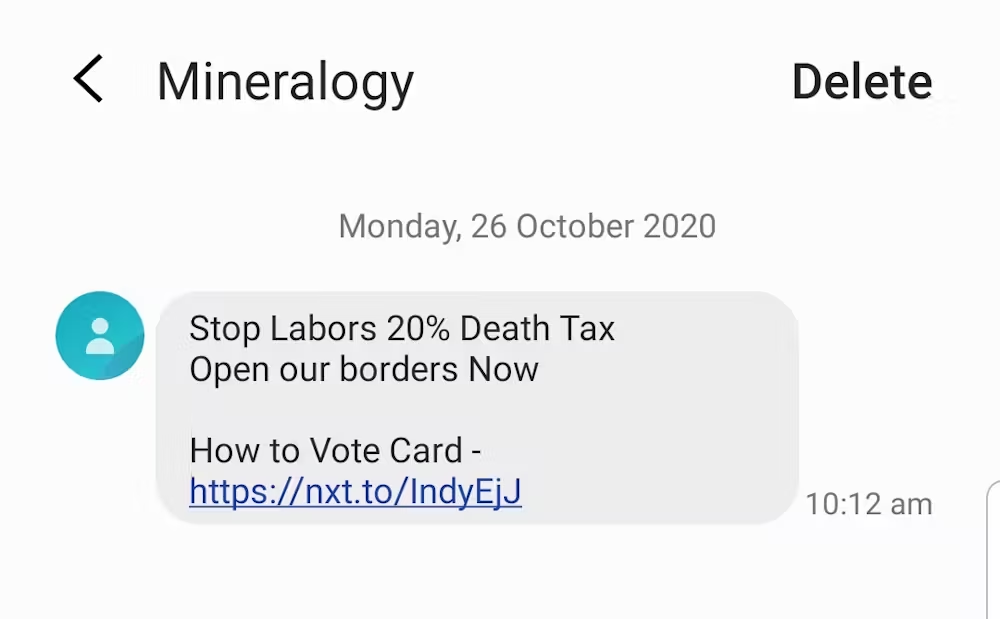

The Australian Communications and Media Authority confirms that political text messages during election campaigns are exempt from most spam and telemarketing rules. The only requirement is that messages must identify who authorized them, which explains why you’ll see names like Harold Fong appearing on Trumpet of Patriots texts.

How Campaigns Access Your Personal Information

The mystery of how political parties obtain phone numbers for their mass texting campaigns reveals the extent of data collection happening behind the scenes. While the Australian Electoral Commission doesn’t provide phone numbers to political parties, campaigns have multiple avenues for acquiring personal information.

The electoral roll serves as one source, though it doesn’t contain phone numbers. Incumbent politicians can repurpose contact information obtained through constituent interactions, thanks to the political exemptions that allow them to use this data for campaigning purposes. Data brokers represent another significant source, as these firms harvest, analyze, and sell large quantities of personal information and profiles to anyone willing to pay.

Major political parties maintain sophisticated voter databases that have grown increasingly complex over the years, combining information from multiple sources to create detailed voter profiles. Some smaller operations take more haphazard approaches, with former MP Craig Kelly claiming to use software that randomly generates phone numbers for mass texting campaigns.

The Push for Reform

The current system has drawn criticism not just for its annoyance factor, but for its potential to spread misinformation. Reports of misleading “push polling” texts and fake postal vote applications distributed via SMS highlight the broader vulnerabilities created by political exemptions. The rise of generative AI makes it even easier to produce misleading content quickly and cheaply, amplifying these concerns.

In 2022, the Attorney General’s Department proposed significant reforms to narrow the political exemptions as part of broader Privacy Act updates. These changes would require political parties to be more transparent about their data operations, provide voters with unsubscribe options for targeted advertisements, avoid targeting based on sensitive information, and handle data in a “fair and reasonable” manner.

The proposed reforms recognize that voter privacy plays an essential role in maintaining a functioning democratic system. However, the government has not committed to implementing these changes, and bipartisan support appears unlikely despite growing public frustration with the current system.

What This Means for Voters

Nearly three-quarters of Australians incorrectly believe that political parties must comply with privacy laws, according to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s 2023 community attitudes study. Eighty-two percent of respondents said political parties should be subject to these rules.

Until legislative changes occur, voters have limited recourse against unwanted political messages. The exemptions that allow this practice reflect a balance struck decades ago between protecting political communication and respecting voter privacy. However, as digital communication has evolved and data collection has become more sophisticated, this balance increasingly favors political parties at the expense of voter privacy and choice.

The frustration expressed by voters receiving multiple daily messages from parties like Trumpet of Patriots reflects a broader disconnect between public expectations and legal reality. While the constitutional protection of political communication remains important, the current system provides political parties with what critics describe as a “captive audience” without meaningful consent or opt-out mechanisms.