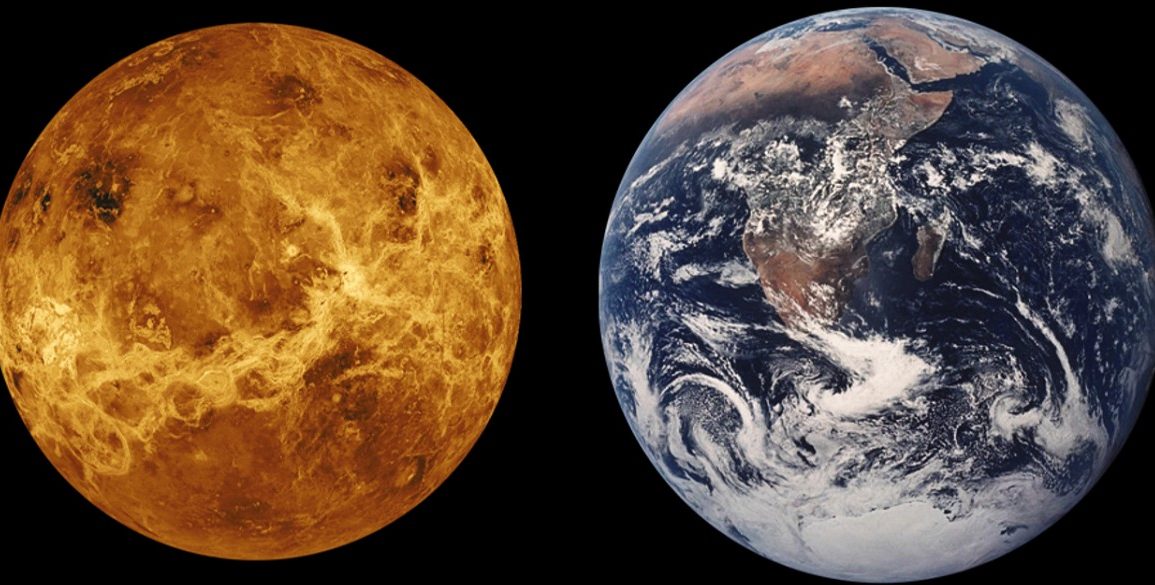

For decades, scientists speculated that Venus, often called Earth’s “evil twin,” may have once been a hospitable planet.

With its similar size and proximity to Earth, some believed Venus was home to cooler temperatures and vast oceans of liquid water.

However, recent research casts doubt on this theory, suggesting Venus has always been an arid, uninhabitable world.

A study led by Tereza Constantinou at the University of Cambridge analyzed the chemistry of Venus’s atmosphere to understand its interior water content.

The findings reveal Venus’s volcanic activity is “dry,” indicating the planet’s interior is devoid of significant water.

This challenges the notion that Venus ever had the liquid oceans considered essential for Earth-like life to emerge.

During Venus’s early formation, the planet was enveloped in a molten sea of magma. If the magma had cooled quickly, it could have trapped water, leading to surface oceans.

However, Constantinou explained that slow cooling would have left the water as atmospheric steam, resulting in a dry planetary interior.

By examining the steady balance of atmospheric substances replenished by volcanic eruptions, the researchers confirmed a scarcity of water emissions.

This suggests that Venus’s environment has been inhospitable throughout its history.

Despite these findings, the study doesn’t entirely rule out the possibility of life, particularly in Venus’s acidic clouds.

However, the lack of Earth-like conditions significantly narrows the scope for habitability.

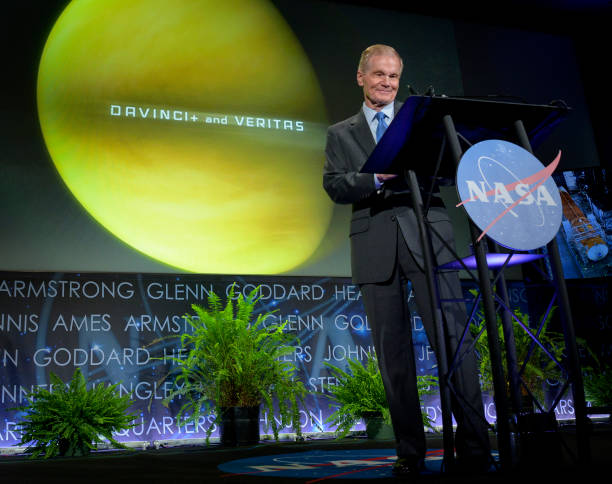

NASA’s upcoming DaVinci mission, set to explore Venus later this decade, could provide further clarity.

The mission will conduct flybys and deploy a surface probe to analyze the planet’s atmospheric and geological composition.

Understanding Venus’s history not only sheds light on the evolution of habitability within our solar system but also aids in identifying potentially habitable planets beyond it.

Constantinou emphasizes the importance of studying Venus and Earth as a “natural laboratory” to uncover the dynamics of planetary habitability.