Kerry Plowright was enjoying a quiet evening at home in Kingscliff, New South Wales, last year when a sudden alert on his phone warned him of incoming hail.

The warning came too late for him to fully prepare, but he acted quickly to move his cars under protective canvas sails, avoiding significant damage. His experience underscores a broader issue: Australians are facing increasingly extreme weather with often insufficient warnings.

This summer has already been marked by dramatic weather events, and forecasts suggest a second tropical cyclone might hit Queensland soon.

According to the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), a potential tropical cyclone named Kirrily could make landfall on the Queensland coast by the end of the week.

The advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) in weather forecasting promises improved accuracy and earlier warnings, but it also raises questions about its reliability and integration with traditional methods.

The Albanese government has initiated an inquiry into the Bureau of Meteorology’s (BoM) warnings, driven by concerns from local councils and other stakeholders about the accuracy and timeliness of some alerts.

In contrast, Plowright’s hail warning came from Early Warning Network, a company he founded. This company uses data from radars and remote sensors to issue alerts on extreme weather events such as heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and flooding. Their innovative approach includes the use of AI to enhance forecasting capabilities.

Early Warning Network analyzes data from various sources to provide timely alerts. Unlike traditional methods that rely on expensive and complex supercomputers, Plowright’s firm leverages AI to make weather forecasting more accessible and affordable.

He believes that AI will revolutionize weather and climate predictions, offering faster and more detailed information without the high costs typically associated with advanced forecasting.

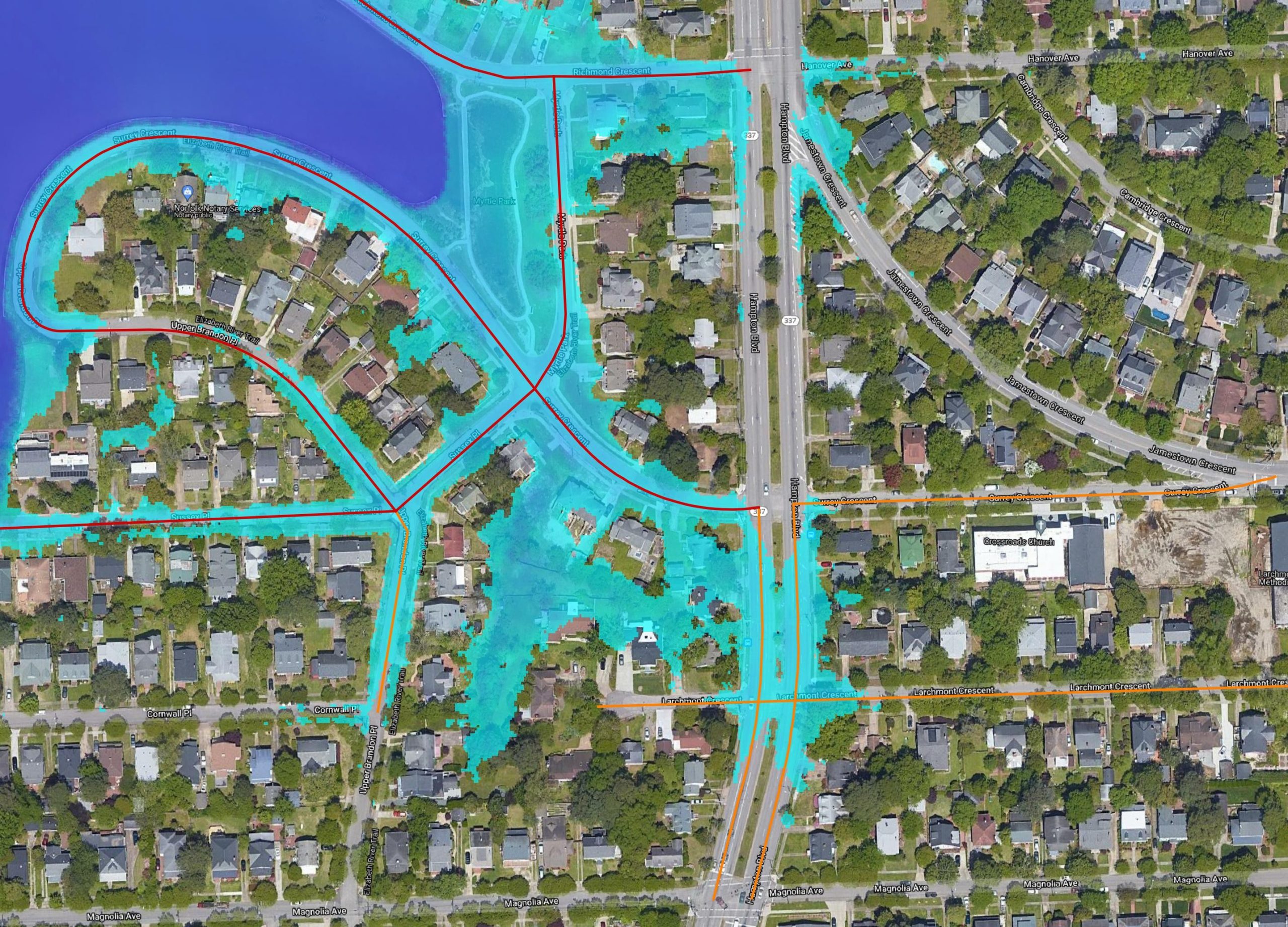

Juliette Murphy, a water resources engineer and founder of FloodMapp, shares this optimism about AI’s potential. After witnessing the impact of devastating floods in Queensland and Calgary, she created FloodMapp to give communities better preparedness for floods.

FloodMapp combines machine learning with traditional hydrological models to process large datasets quickly, providing more accurate and timely flood predictions. This tool is used by emergency services to make critical decisions, such as evacuating homes and closing roads.

The Bureau of Meteorology has been exploring AI capabilities for several years. A spokesperson noted that AI research is part of the bureau’s ongoing efforts to enhance its services for government, emergency management, and the public.

Justin Freeman, a computer scientist who led BoM’s machine learning research before leaving to start his own company, Flowershift, continues to work on AI models that could fill gaps in current forecasting systems. Freeman’s work focuses on geospatial models that can provide localized forecasts, particularly for remote areas.

He envisions a future where AI-driven models become increasingly sophisticated, improving weather predictions and offering practical applications for various industries.

Despite the excitement surrounding AI, there are limitations and challenges. Some BoM scientists and climate researchers express caution regarding the reliance on AI models like Google’s GraphCast and Nvidia’s FourCastNet.

While these models show promise, especially in downscaling weather data to finer resolutions, there are concerns about their ability to handle extreme weather events and their reliance on existing data that may have imperfections.

Sanaa Hobeichi, a post-doctoral researcher at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, acknowledges the benefits of AI models despite their limitations.

Traditional climate models often provide coarse resolutions, which can be inadequate for detailed local predictions. AI models, such as Google’s GraphCast, offer finer resolutions that can be more useful for specific areas.

However, these models can also inherit and potentially amplify the flaws of traditional models they are based on.

Jyoteeshkumar Reddy Papari, a researcher at CSIRO, notes that while AI models are gaining traction, they must be validated and refined.

The ECMWF, initially skeptical of AI, has begun experimenting with its models and displaying others from different organizations.

Some countries with less advanced meteorological infrastructure are turning to publicly available AI models for their forecasts, highlighting the technology’s potential to provide valuable information where traditional systems are lacking.

Google researchers have reported that GraphCast significantly outperforms traditional systems in many cases, including predicting hurricane trajectories more accurately. As AI models continue to evolve, they may offer significant improvements in weather forecasting, though the technology is still in its early stages.

Matthew Chantry, the ECMWF’s machine learning coordinator, views AI as a promising complement to traditional forecasting methods.

While AI models can reduce the computational resources needed for forecasts, they are not yet a complete replacement for existing systems. The integration of AI could lead to more cost-effective forecasting and a better understanding of low-probability, high-impact events.

As climate change accelerates and extreme weather events become more frequent, the need for accurate and timely forecasts becomes even more critical.

AI models have the potential to enhance our ability to predict and respond to these events, though they must be carefully developed and validated to ensure their effectiveness. The continued advancement of AI in weather forecasting could play a crucial role in improving preparedness and resilience in the face of increasingly unpredictable weather patterns.